In the deep and seemingly endless expanse of Kenya’s arid rangelands, where the golden sun scorches the parched earth and the acacia trees stand as quiet sentinels over the land, a unique story of resilience unfolds every single morning. Before the rooster crows in the quiet serenity of Kajiado and Narok counties—home to the proud Maasai community—small feet begin to move.

Children, barely taller than their walking sticks, begin the long, winding journey to school, their tiny shadows merging with those of the morning gazelles that skip past thorny bushes.

The road is not paved, and neither is it short; it stretches far through dust, dry riverbeds, and sometimes hostile terrain. Yet, these children walk on—not because they must, but because they dare to dream.

The landscape is breathtaking in its beauty and brutal in its demands. The distant mountains shimmer under the heatwaves, cattle bells echo through the hills, and dust devils spiral in silence.

Here, life depends on adaptation. The Maasai have, for generations, thrived in this ecosystem through nomadic pastoralism. But as climate change intensifies and modernization slowly creeps in, the traditional ways are being tested, and education has emerged not only as a beacon of hope but as a tool of survival.

In this serene, drought-streaked backdrop, school-going children have become quiet revolutionaries—braving hunger, thirst, long distances, and often cultural expectations to sit under the shade of a tree or in a poorly constructed classroom to learn how to write their names, recite poems, or dream of being doctors, teachers, and lawyers.

Their struggles are real and many, and their triumphs are often invisible. In some villages, classrooms are made of mud and cow dung, with open roofs that leak when the rains come, though the rains rarely come.

Desks are shared by three or more students, and textbooks are a luxury. In one school, children rotate a single pair of shoes on different days. In another, students carry water in reused cooking oil bottles for their own use—and to spare a little for the school kitchen.

These are not tales designed to invoke pity, but reality served raw. It is within these humble spaces that learning thrives and hope is nurtured.

Yet, amid these challenges, the resolve of the Maasai children remains unbroken. Eleven-year-old Naserian, for example, walks eight kilometers each morning with her younger brother in tow.

She carries a plastic bag containing her books and a half-roti from the previous night’s dinner. Her eyes shine with determination as she speaks of wanting to be a doctor so she can return and build a clinic for expectant mothers in her village.

“We lose many women because we have to walk too far for help,” she says, not in despair, but with the quiet authority of someone who has seen too much for her age. Her dreams are not shaped by fantasy but by necessity.

Education in the dry lands is not just about school—it is about transformation. It represents a departure from cycles of poverty and illiteracy. For girls especially, the journey to school is often a rebellion against deeply entrenched customs.

Early marriages, female genital mutilation, and domestic chores often compete with school attendance. Yet, there is a growing wave of enlightenment, as more Maasai elders, leaders, and mothers recognize the changing times.

Schools now represent not a threat to culture, but a shield to preserve it in an evolving world. Female education is increasingly embraced, not just by policy makers but by local warriors who once viewed it with suspicion.

The legal framework backing this movement is robust. Article 53(1)(b) of the Constitution of Kenya states that every child has the right to free and compulsory basic education.

Right to Education

The Basic Education Act of 2013 mandates that the government ensure no child is left behind due to geographic, economic, or cultural barriers.

Furthermore, Kenya is a signatory to several international legal instruments such as the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), which provides that primary education must be made compulsory and available free to all.

These laws, while noble in text, still face challenges in implementation—particularly in marginal areas like the Maasai territories, where enforcement often lags behind policy intentions.

Teachers posted to these remote regions are often untrained, underpaid, and overwhelmed. Yet, many have grown to love their role as mentors. Mr. Lemayian, a primary school teacher in Mashuuru Division, speaks proudly of his pupils. He arrived in the area on a one-year contract and ended up staying for seven.

“These children are hungry—not just for food but for knowledge,” he says. Despite not having access to electricity or internet, he uses storytelling and songs in the Maa language to teach English and mathematics.

“Education must make sense to them. If I teach them using examples of airplanes and elevators, they won’t relate. But if I talk about cattle, rivers, and the moon, their eyes light up,” he says.

The involvement of civil society has also played a pivotal role. Organizations such as AMREF, World Vision, and local faith-based groups have been instrumental in constructing classrooms, providing school meals, and setting up boreholes.

The implementation of solar-powered tablets in a few pilot schools has shown promise in bridging the technological divide. However, infrastructural challenges remain massive.

Many schools are still too far apart. Children wake at dawn to begin treks that could take two hours or more. This journey becomes even more dangerous during the dry seasons when wild animals come closer to settlements in search of water.

Yet, the serenity of the Maasai land hides more than struggle; it sings stories of quiet progress.

In Olgulului village, a girls’ empowerment school led by a former child bride has witnessed a 60% increase in female enrollment over the past three years.

These schools double as safe havens, offering not just education but shelter, food, and mentorship. The community elders have begun to play a more active role, using their influence to protect school-going children and punish those who attempt to lure them into early marriages.

“When one girl succeeds, she carries the whole village with her,” an elder explains.

The duality of this existence—caught between tradition and progress—offers a unique lens through which Kenya’s education crisis can be viewed.

Here, education is not only about passing exams or earning degrees; it is about reimagining futures. It is about rewriting a narrative in which geography no longer dictates destiny. And at the center of this movement are the children—barefoot, sun-kissed, and determined.

To continue the journey of these resilient learners is to uncover a deeper truth about the intersection of hardship, hope, and human potential.

The Maasai plains, rich in cultural heritage and environmental beauty, also bear the scars of exclusion—decades of systemic marginalization that have rendered essential services like education a privilege rather than a right.

Yet within this disparity, children rise, teachers persist, and communities slowly transform.

At the core of this transformation is the unshakable belief that education is more than literacy—it is liberation. Liberation from generational poverty, from the oppressive chains of ignorance, from cultural practices that deny children their rights.

What Education Means to Maasai Children

To the Maasai child, school is not merely a building with walls and chalkboards. It is a sanctuary—a sacred space where identity meets inquiry, where tradition dialogues with transformation.

Consider the case of Nalangu, a fifteen-year-old girl from Ewaso Ng’iro. Her journey is emblematic of both the struggle and the shift occurring in Maasai land.

When she turned twelve, a suitor was chosen for her in accordance with cultural practice. A cow exchange had been agreed upon; her marriage was only weeks away.

But her mother, educated to Class Four and now working as a community health volunteer, stood firm. Risking societal backlash and familial rejection, she insisted that Nalangu continue with her education.

The community responded with silence, some with ridicule.

But today, Nalangu is in Form Two, a prefect at her school, and an aspiring lawyer who wants to advocate for girls’ rights across Kenya.

Her story is a declaration—a child’s future should never be determined by livestock valuations or outdated customs, but by her dreams and her potential.

Such stories are increasingly echoed across Maasai land, driven by grassroots activism, judicial awareness campaigns, and government policy.

County governments have begun to play a more aggressive role in education provision, especially after the 2010 Constitution devolved certain education-related responsibilities.

In Kajiado, the County Education Fund sponsors needy but bright students, constructing boarding facilities for girls vulnerable to early marriages.

In Narok, cultural mediators—often retired elders—are deployed to schools to explain the importance of education in the Maasai language, linking it to moral and spiritual values cherished by the community.

These efforts, while noble, remain insufficient unless supported by national-level budgetary commitments and infrastructural upgrades.

The gap between urban and rural education in Kenya continues to widen, especially in historically neglected regions like Maasai land.

Literacy in Semi-Arid Areas Compared to Urban Places

A 2024 report by the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics revealed that while literacy rates in urban centers like Nairobi and Mombasa stand above 90%, parts of Kajiado and Narok still hover around 58%.

This disparity is not due to a lack of intelligence or ambition, but a lack of access, resources, and inclusive policies.

Classrooms in towns boast smart boards and internet connectivity; those in dry lands struggle to print exam papers.

Such injustice must be addressed as a constitutional concern under Article 43, which enshrines the right to education as a component of social and economic rights.

Infrastructure is not the only barrier—climate volatility adds a cruel dimension to the crisis. Frequent droughts dry up water pans, force families to migrate, and drive children out of schools into survival mode.

The erratic rainfall has even made the school calendar unreliable.

Term beginnings are often postponed as parents weigh between feeding their families or walking children to distant schools.

The long dry seasons, once predictable, now stretch beyond expected months, exhausting both livestock and human energy. In such conditions, schools become casualties, not priorities.

Yet, even in this chaos, innovation blooms.

One promising initiative is the “School on Wheels” project launched by a collaboration between a youth-led organization and a Danish development partner.

This program uses solar-powered mobile classrooms—modified trucks that traverse villages, providing lessons to children whose families are constantly on the move.

The classrooms are equipped with foldable blackboards, mobile libraries, and charging stations. Teachers rotate in weekly shifts, staying with pastoral families to teach core subjects.

Feedback from the pilot program has been overwhelmingly positive, especially among young boys who had long dropped out to herd livestock.

Digital inclusion also offers a glimmer of possibility. Though internet connectivity remains scarce in many regions, satellite internet and solar charging hubs are slowly being introduced in select schools.

The Ministry of ICT, in collaboration with private stakeholders, is testing low-bandwidth e-learning platforms that can operate offline.

These platforms contain interactive lessons in English, Kiswahili, and Maa.

For the first time, children in these areas are solving math puzzles, watching biology videos, and even participating in virtual debates with peers in Nairobi and Eldoret. While the digital divide is vast, steps are being taken, one rural signal tower at a time.

Also Read: KUCCPS Courses with the Lowest Cluster Points and Universities Offering Them

Still, for every success, a crisis looms. The harsh irony of Maasai land is that while it is rich in heritage, its children are often robbed of their birthright to knowledge.

The government must do more—construct more schools, employ more teachers, build safe boarding facilities, and tailor curricula to fit nomadic life.

Legal redress mechanisms must be accessible to families whose children are denied education.

Special provisions should be made in national development plans to reflect the lived reality of arid regions.

Education in Maasai land is not a charity—it is a constitutional, legal, and moral obligation.

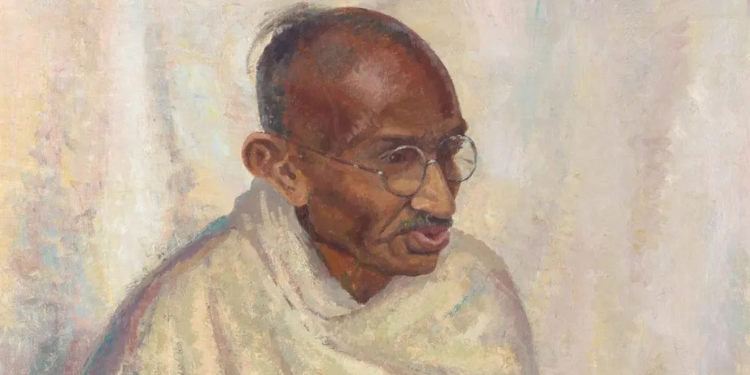

Scholars such as Prof. Yash Pal Ghai have long emphasized the principle of substantive equality, which recognizes that equal treatment is not enough in unequal circumstances.

In his works on constitutionalism and social justice, Ghai argues that marginalized communities require affirmative action to level the playing field.

In the context of Maasai education, this means scholarships, food programs, teacher incentives, and curriculum reform. Anything less is a betrayal of the promise of the 2010 Constitution.

The resilience of Maasai children should not be glorified as heroism but interrogated as a symptom of national neglect.

No child should have to walk barefoot for ten kilometers in blistering heat just to access a basic human right.

Similarly, no teacher should have to teach sixty students under a tree.

No girl should have to choose between her books and her body.

Kenya has the resources, the legal tools, and the human capital to fix this. What is lacking is political will.

But even in the absence of that will, the children persist.

They tie tattered uniforms with sisal strings, singing songs to remember multiplication tables.

Besides, they sit on stones, lean against trees to read their notes and scribble essays on old newspapers.

In their eyes is not just hope, but faith. Faith that someday, this nation will look back and say: these children mattered. Their dreams mattered.

Their struggle was not in vain.

As the sun sets over the expansive plains, painting the sky with hues of orange and gold, the sound of a chalk scratching a borrowed board echoes in the quiet dusk.

A child, lit by firewood and ambition, reads aloud from a tattered book. She is not afraid of the dark. She is learning how to write her own future.

Also Read: Exploring the Roots of Stupidity: Psychology of What Lies Behind Irrational Opinions

The Unyielding Flame of Maasai Children

In the heart of the dry Maasai land, where the acacia trees stretch their thorny arms toward the sun and the red soil breathes stories of both glory and grief, a quiet revolution is underway—led not by generals or governors, but by school-going children.

Against a backdrop of climate adversity, historical neglect, patriarchal customs, and infrastructural decay, they rise.

With cracked feet, sunburned skin, and dreams taller than the hills of Ol Doinyo Lengai, they walk—miles, hours, days—towards blackboards, towards books, towards freedom.

Their resilience is not romantic; it is radical. It is a protest against every policy that has failed them, every budget cut that ignored them, every voice in high places that spoke about them but never to them.

These children are not statistics in a policy brief. They are living proof that even in forgotten corners of this nation, the human spirit—when fueled by education—burns unquenchably.

But their strength must not be exploited as a reason to delay justice.

Kenya’s legal framework, especially Article 53(1)(b) of the 2010 Constitution, guarantees every child the right to free and compulsory basic education. Article 27(6) mandates affirmative action to redress past disadvantages.

The Children Act (2022), the Basic Education Act (2013), and international obligations like the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child all demand that Maasai children be protected, taught, and elevated—not ignored.

Still, the law alone cannot educate. It must be accompanied by tangible reforms—boarding facilities for pastoralist communities, culturally sensitive curricula that harmonize tradition with transformation, deployment of qualified teachers to arid zones, sustainable food programs, and solar-powered digital learning.

What Govt Should Do

The government must increase its investment in arid counties. County assemblies must pass education-specific bills. Civil society must partner with elders, not bypass them.

And above all, the nation must listen—not to speeches in air-conditioned halls, but to the whispers of children learning beneath the trees.

To the teachers who refuse to abandon the blackboard, to the parents who sell their only cow for a uniform, to the girls who fight through stigma and silence, and to the boys who carry books in sacks once meant for herding—they are Kenya’s unsung architects.

And to the child who sits under a tree with a borrowed pen, daring to dream amid droughts and dust—she is not just studying. She is rewriting the future.

In the serenity of dry Maasai land, where the sky is wide and the land stubborn, there burns an unyielding flame: the hope of education. Let us not let that flame die.

Let us guard it with policy, fuel it with resources, and honor it with action.

For in every Maasai child who learns, this country finds its soul again.

Follow our WhatsApp Channel and X Account for real-time news updates.

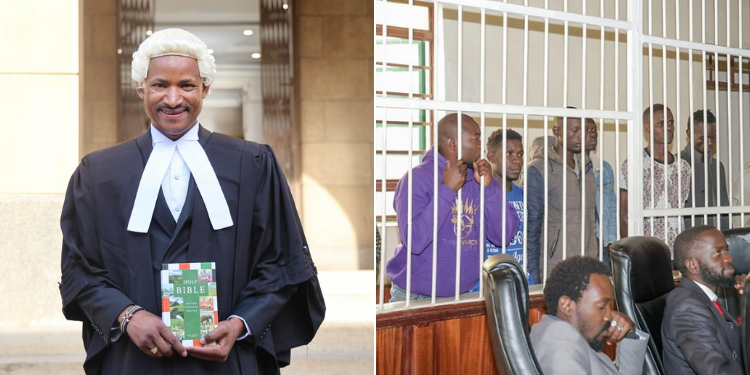

The Writer, Omwansa Onduko is a 2nd year Student at Kabarak University School of Law